Key Takeaways

- Understand the difference between Pointing (Type 1) and Claiming (Type 2) candidates.

- Learn why Box/Line Reduction is the essential bridge to expert-level puzzles.

- Discover how Snyder Notation can naturally reveal advanced patterns.

You have mastered the basics of Sudoku. You can spot Naked Singles and Hidden Singles with ease, and you have no trouble filling out a "Moderate" grid. But then, it happens—the "wall." You reach a point where no more obvious numbers appear, and the standard scanning methods fail you. This is the moment where most casual players give up, but it is also where the real beauty of the game begins. To advance, you must master the sudoku box line reduction and its sibling, the pointing pair.

As a cognitive neuroscientist, I have studied how the human brain processes these specific patterns. These strategies, collectively known as "Locked Candidates," represent a significant shift in mental processing. You move from looking for where a number is to proving where a number cannot be. This shift in spatial reasoning is not just a game strategy; it is a workout for your prefrontal cortex, enhancing your ability to filter out irrelevant information in complex environments.

In this comprehensive guide, we will break down the mechanics of Locked Candidates, explore the statistical necessity of these moves in high-level play, and look at the 2026 trends shaping how we learn these brain-boosting patterns.

Understanding Locked Candidates: The Secret to Hard Puzzles

Before we dive into the specific mechanics of sudoku box line reduction, we must understand the umbrella term: Locked Candidates.

A Locked Candidate occurs when the possible positions for a digit within a specific "unit" (a row, column, or 3x3 box) are restricted in a way that allows you to eliminate that digit from other intersecting units. In simpler terms, the numbers are "locked" into a specific configuration that has ripple effects across the board.

According to a 2025 study of over 4,000 minimal puzzles, [Naked Pairs in Sudoku]({path: '/blog/naked-pairs-sudoku-how-find-use'}) and Locked Candidates are the most frequently used intermediate strategies. While 48.4% of randomly generated puzzles are solvable with simple singles, once you step into "Hard" territory (like the New York Times Hard difficulty), the incidence of Locked Candidates jumps significantly.

Pointing Pairs and Triples (Locked Candidates Type 1)

The most common form of Locked Candidates is the Pointing Pair (or Triple). This technique is often the first "real" strategy a player learns after mastering the basics.

The Logic of Pointing

A Pointing Pair occurs when all the potential spots for a specific candidate within a 3x3 box are aligned in a single row or column.

Because the rules of Sudoku state that the digit must appear once in that box, and because the only available spots for it are in that specific line, we can logically conclude that the digit cannot appear anywhere else in that same line outside of that box.

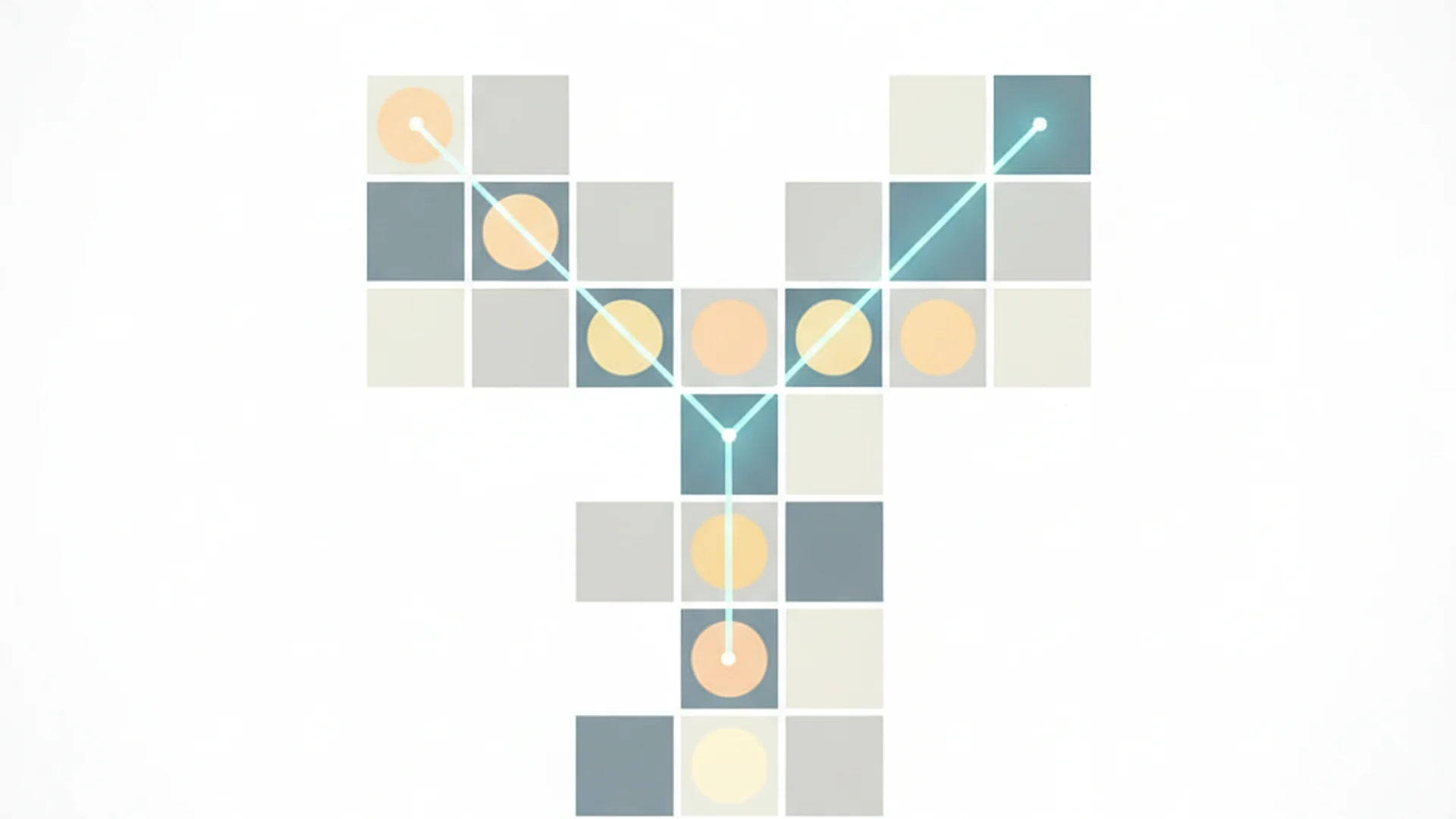

Visualizing the Move

Imagine Box 1 (top left). You are looking for where the number 5 can go. Through basic scanning, you realize the 5 in Box 1 can only fit in two cells, and both of those cells happen to be in Row 1.

Even though you don't know which of those two cells will eventually hold the 5, you know with 100% certainty that the 5 for Row 1 is "trapped" inside Box 1. Therefore, you can safely remove "5" as a candidate from every other cell in Row 1 (in Boxes 2 and 3).

The Power of Box/Line Reduction (Locked Candidates Type 2)

While Pointing Pairs start with the box and "point" to the line, sudoku box line reduction (also known as "Claiming") works in the opposite direction. This is often harder for the human eye to spot because it requires scanning a full row or column rather than a small box.

The Logic of Claiming

Box/Line Reduction occurs when all the possible spots for a candidate in a row or column are concentrated within a single 3x3 box.

If Row 5 only has two available spots for the number 7, and both of those spots are inside Box 4, then Box 4 must get its 7 from Row 5. Consequently, the number 7 cannot exist in any other cells within Box 4 that are not part of Row 5.

Example: The "Row Claim"

- You scan Row 8 for the number 2.

- You find that the number 2 can only go in two cells in Row 8.

- Both of these cells are located within Box 9 (the bottom right box).

- Logic: Since the 2 for Row 8 must be in one of those two cells, Box 9 is now "claiming" that 2.

- Elimination: You can now remove the number 2 from every other cell in Box 9 (in Rows 7 and 9).

Statistical Breakdown: Why These Techniques Matter

In the world of competitive Sudoku, the jump from "Moderate" to "Hard" is mathematically defined by the necessity of these techniques. As we can see in the table below, the reliance on basic [Sudoku Rules Explained]({path: '/blog/sudoku-rules-explained-everything-need-know'}) is not enough once you reach the top tier.

| Difficulty Level | Solvable by Singles | Requires Locked Candidates | Requires Advanced (X-Wing/Fish) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | 98% | 2% | 0% |

| Moderate | 65% | 30% | 5% |

| Hard | 15% | 65% | 20% |

| Expert | 5% | 45% | 50% |

Data from 2025 research suggests that roughly 19.1% of "Hard" puzzles use Locked Candidates as their "ceiling"—meaning if you know this technique, you can solve the puzzle without ever needing complex strategies like [Advanced Sudoku Techniques: X-Wing and Swordfish]({path: '/blog/advanced-sudoku-techniques-x-wing-swordfish'}).

Expert Strategies for Spotting Reductions

How do pros like those at the World Sudoku Championship find these patterns so quickly? It comes down to systematic unit checking and "chute" scanning.

1. Scan the "Chutes" First

A "chute" is a group of three boxes in a row (horizontal chute) or a column (vertical chute). If a number is already placed in two of the boxes in a chute, immediately check the third box. Often, the remaining spaces will form a Pointing Pair that clears candidates in the other two boxes, potentially triggering a chain reaction of placements.

2. Intersection Analysis

Look at "intersections" where a heavily populated row meets a sparse box. When a box has many numbers filled in, the remaining empty cells are forced into specific lines. This is the "hunting ground" for Box/Line Reductions.

3. Systematic Unit Checking

After placing a new digit, don't just look for the next number. Immediately re-check the affected row, column, and box for any newly created Locked Candidates. Every number placed changes the "candidate landscape," potentially creating a Pointing Pair where there wasn't one a moment ago.

2026 Trends: The Evolution of Sudoku Learning

As we move into 2026, the way we learn and execute these strategies is changing due to technological advancements.

- Human-Centric AI Benchmarks: In 2025, researchers (including Sakana AI) launched new benchmarks to see if AI can solve puzzles using "human-like" logic. Instead of brute-force guessing, these AIs are programmed to use sudoku box line reduction, helping developers create better hints for learning apps.

- AR Solving Platforms: Experimental 2026 VR and AR platforms allow players to "layer" pencil marks in 3D. This makes it significantly easier to visualize how a box "points" across the grid, as the line literally glows or highlights in your field of vision.

- 2026 World Sudoku Championship (India): The upcoming tournament is highlighting "Variant Sudokus." In these games, Pointing Pairs logic is combined with arithmetic constraints (like Renban or Even-Odd). Mastering the base logic now is essential for those looking to compete in these new, complex formats.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even seasoned players can stumble when applying these techniques. Here are the most common pitfalls I see in my research into cognitive error patterns.

The "One-Way" Fallacy

Beginners often think that if a pair in a box points to a row, that row must point back to the box. This is incorrect. The logic is unidirectional. You can only clear candidates in the "target" area (where the line or box is being pointed at), not the "source" area.

Missing the "Claiming" Type

As noted earlier, players are naturally better at looking at boxes than lines. Because we are taught [How to Play Sudoku: Step-by-Step]({path: '/blog/how-play-sudoku-step-by-step-beginners'}) by focusing on the 3x3 grids, we often forget to scan the full length of a column to see if a candidate is "claimed" by a box.

The Fish Trap

Don't over-complicate the puzzle. Many players start looking for X-Wings or Swordfish because they feel the puzzle is "hard." In reality, a simple sudoku box line reduction would have cleared the path. Always check intersections before looking for complex "Fish."

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between Pointing and Claiming?

Are Pointing Triples different from Pointing Pairs?

Can Box/Line Reduction solve the whole puzzle?

How do I know which cells to clear?

Why is Snyder Notation recommended for this?

Conclusion: Elevating Your Cognitive Game

Mastering sudoku box line reduction is more than just a way to solve a puzzle; it is an exercise in deductive reasoning that strengthens the neural pathways associated with logical thinking and pattern recognition. By learning to see the "hidden" relationships between boxes and lines, you transition from a player who follows rules to one who understands the underlying structure of the grid.

As you practice, remember to look for the "Locked Candidates" before jumping to advanced fish patterns. Use Snyder notation to keep your grid clean, and always re-check your intersections after every number you place.

For more insights into how puzzles can improve your mental health, read my article on [Brain Health and Puzzles: Science of Cognitive Gaming]({path: '/blog/brain-health-puzzles-science-cognitive-gaming'}).